I am a PhD candidate in the Department of Psychology at UC Berkeley, supervised by Rich Ivry. I am broadly interested in the flexibility of human learning. I build cognitive and neural models to understand how the brain supports multiple learning processes and how these systems interact to enable adaptive behavior. My early PhD work focused on how the sensorimotor system operates under multiple sources of uncertainties to support efficient adaptation. I am now extending this work to investigate how we plan movements and make decisions when interacting with other agents under uncertainty. I am also interested in the function of the cerebellum, a brain region historically associated with motor control and learning. I develop models to explore the cerebellum’s role in broader cognitive domains such as timing, intuitive physics, and theory of mind. Here you can find a summary of my current projects.

Theme 1: How the brain adapts to uncertainties in the environment

Our motor system must deal with enormous amounts of noise and uncertainty. For example, our visual and proprioceptive inputs are imperfect, and both the internal state of the body and the external environment are constantly changing. It is impressive that the motor system can still perform accurate movements and generalize skills despite these uncertainties—something that remains a major challenge for robotic systems.

We examine how the motor system adapts to uncertainty across two distinct systems: the implicit recalibration system and the action selection system. The recalibration system corrects for small errors in an automatic way and does not require attentional resources. In contrast, the action selection system is more flexible and can adjust behavior to meet specific task demands.

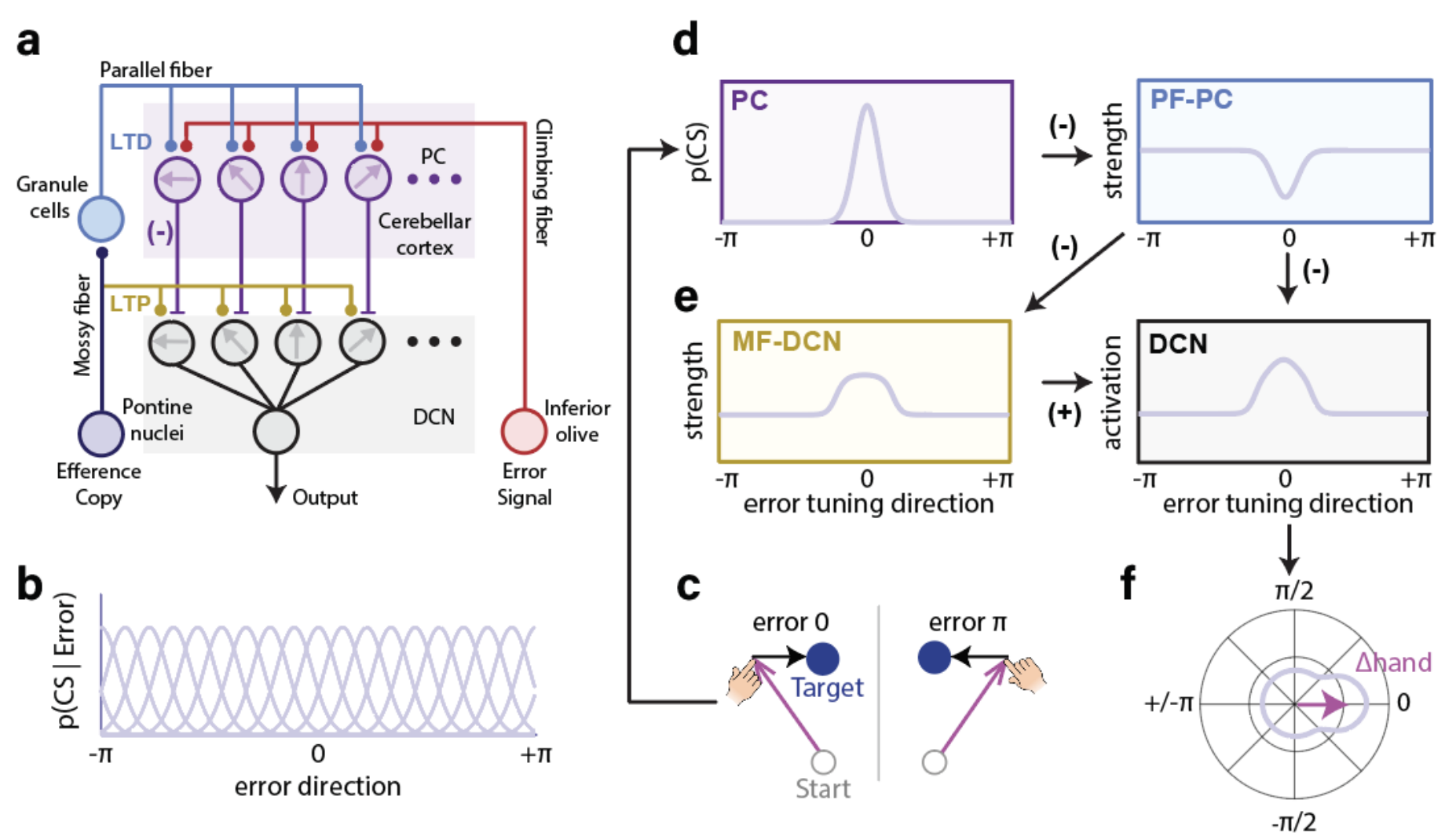

Our recent work suggests that implicit recalibration is insensitive to state noise. However, this system shows unique effects in response to contextual uncertainty. For example, learning is faster but less durable when the environment is volatile; reversal learning is slower than original learning; and relearning is slower, rather than faster, when re-exposed to the same perturbation. We proposed a Cerebellar Population Coding (CPC) model that offers a unified explanation for these contextual effects without invoking contextual inference. The model is a simple two-layer network corresponding to the cerebellar cortex and deep cerebellar nuclei, and contextual effects emerge from the population activation within the model.

To investigate action selection under uncertainty, we developed a novel air-hockey game requiring multi-dimensional motor control and compensation for time-varying wind. The action selection system showed near-optimal modulation, where state noise and volatility had opposite effects on learning rate. Interestingly, participants performed significantly worse when playing a non-motor version of the same task.

Beyond the physical world, another key source of uncertainty comes from other agents. Incorporating this kind of uncertainty requires theory of mind (ToM). However, understanding others’ minds is hard. My current studies focus on how we make decisions in the face of uncertain intentions from other agents.

Theme 2: Target-specific and context-dependent movement biases reveal fundamental computations in motor control

Biases in movement offer a window into the control mechanisms underlying motor behavior. We focus on biases across three time scales:

- Stable target-specific biases

- Biases induced by prior distributions

- Trial-by-trial biases from recent movements

We have developed novel models to explain the origins of these biases.

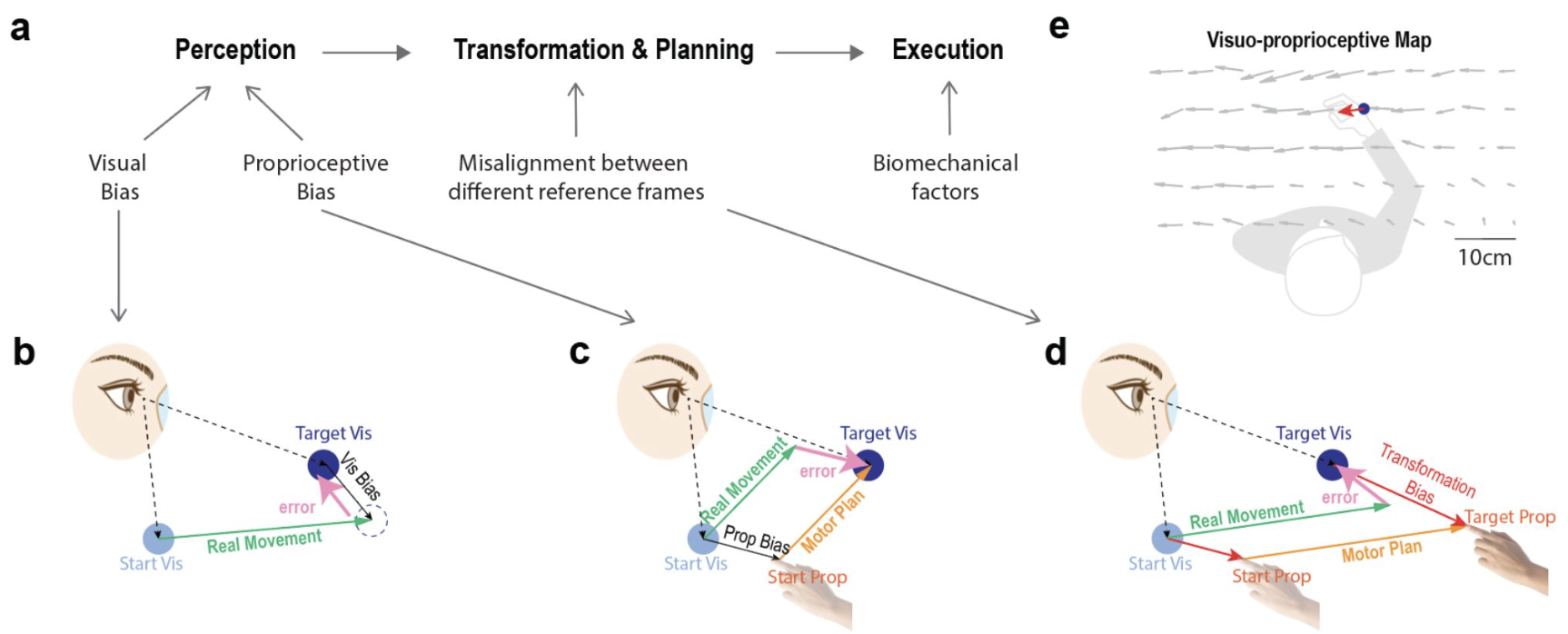

Our work on target-specific bias shows that the pattern reflects a mismatch between the proprioceptive space that encodes hand position and the visual space used for target localization. Modeling suggests that participants perceive the target visually, translate it into proprioceptive space, and then generate a motor plan.

Prior distributions also induce central tendency effects in reaching. However, contrary to prevailing beliefs, we find this bias to be largely non-Bayesian. While the motor bias is modulated by the prior, motor variance is not. Ongoing work is focused on understanding the computational basis of this discrepancy.

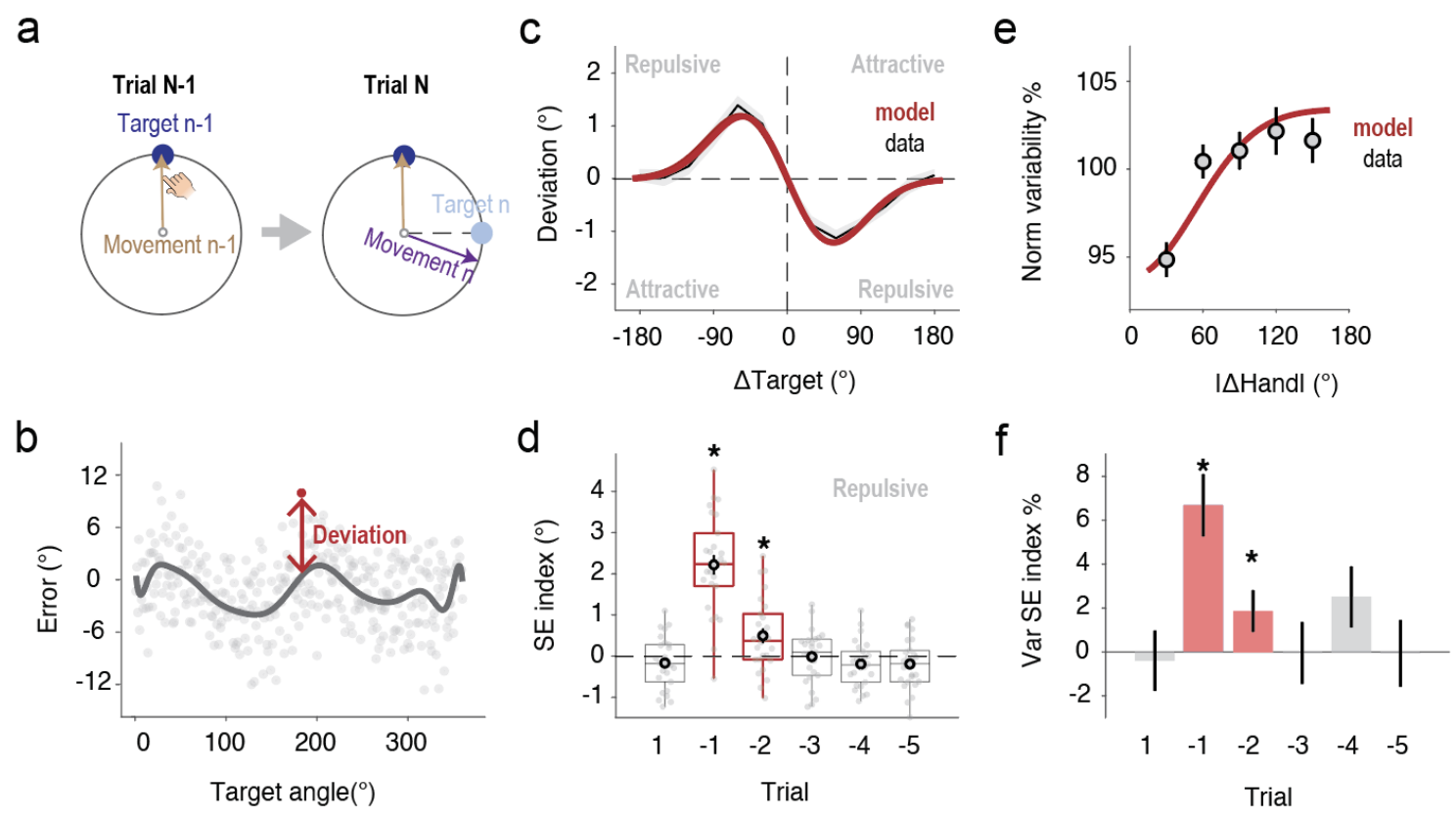

We also identified a novel trial-by-trial bias in which the current movement is biased away from the previous one. The pattern and modulation of this repulsion effect across contexts support an efficient coding mechanism in motor planning. We are now investigating how this repulsive bias interacts with prior-induced central tendency to reveal how the motor system adapts to statistical structure.

Theme 3: How we learn new motor skills

The primary distinction in motor learning lies between adaptation—adjusting a well-trained behavior to compensate for perturbations—and skill learning, which involves creating a new action-outcome mapping from scratch. Most research has focused on the former; little is known about the latter, especially at a computational level.

One of my key interests is understanding the computational mechanisms of motor skill learning. We revisited a longstanding paradox: patients with retrograde amnesia (e.g., HM) can learn mirror-reversed tasks, yet recent studies show the implicit system is surprisingly rigid—even after extended training.

In a recent study, we trained participants for a month on novel sensorimotor maps and observed results that challenge conventional wisdom:

- Implicit adaptation can flip to match new mappings

- There is little interference between old and new maps

- Simple center-out reaching is more effective than complex “skill-like” tasks for inducing adaptation

- Mirror-reversal and rotation tasks produced similar changes in implicit adaptation

We are building neural network models to investigate the distinct roles of the motor cortex and cerebellum in these processes.

Theme 4: Characterize the properties of the implicit sensorimotor recalibration system

The implicit recalibration system exhibits features unlike any other learning system. For instance, our recent study showed that implicit recalibration does not consume attentional resources. Whether participants paid attention to the task, the feedback, or neither had no effect on learning rate—revealing the system’s surprising robustness.

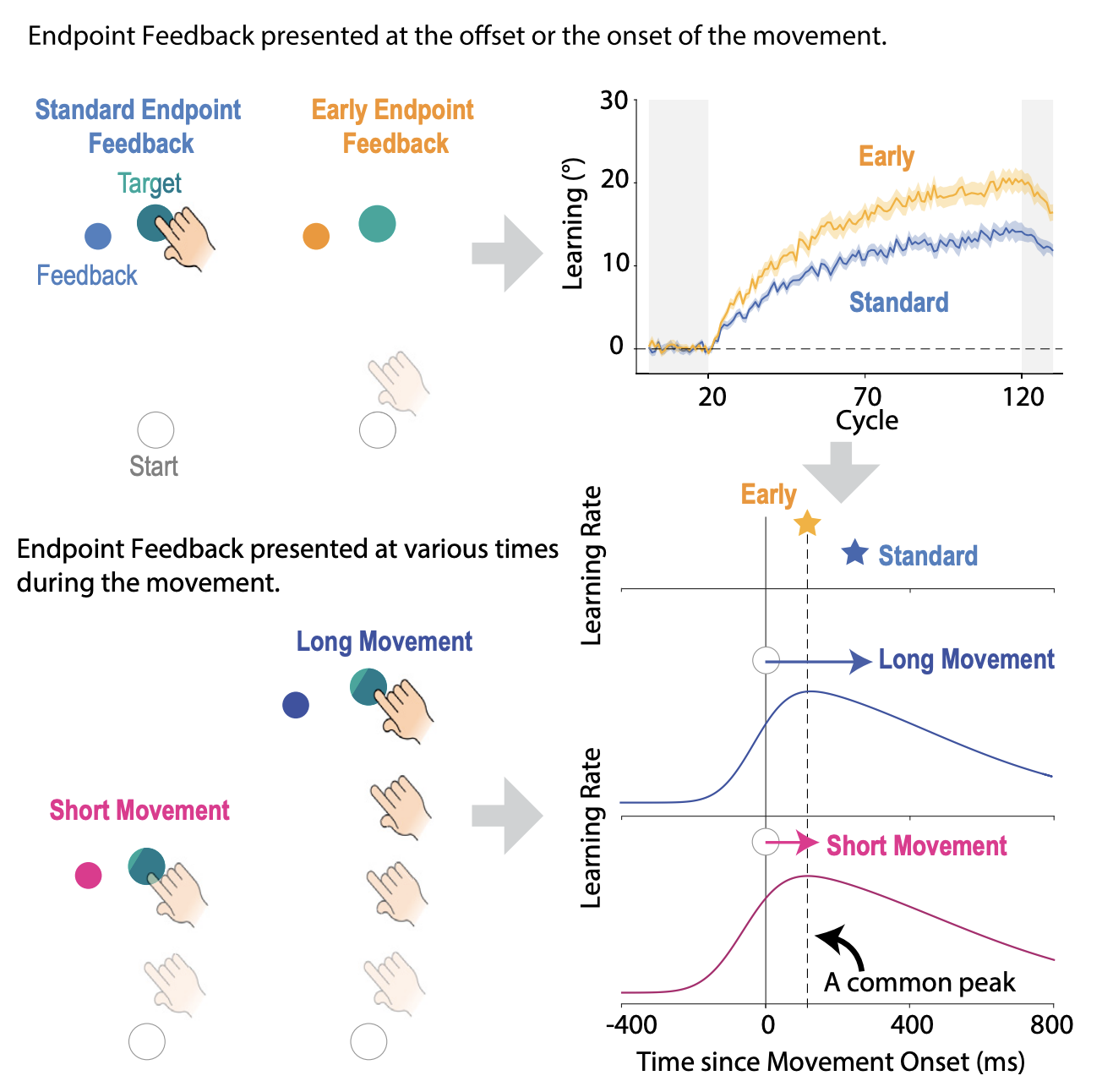

Additionally, learning in this system does not require movement execution. We found that learning is maximized when visual feedback is temporally aligned with motor planning rather than actual movement. Current work involves computational modeling to identify the driving forces behind implicit recalibration, including the role of multisensory integration.

Theme 5: The role of the cerebellum in cognition

While traditionally viewed as a motor structure, the cerebellum is increasingly implicated in cognitive domains such as reward learning and language. However, how the cerebellum contributes to these functions is still unclear.

To address the role of the cerebellum in multiple domains, I conduct neurophysiological and behavioral studies with cerebellar ataxia patients and healthy controls to explore cerebellar involvement in timing, intuitive physics, social perception, and theory of mind. In particular, I focus on the following questions:

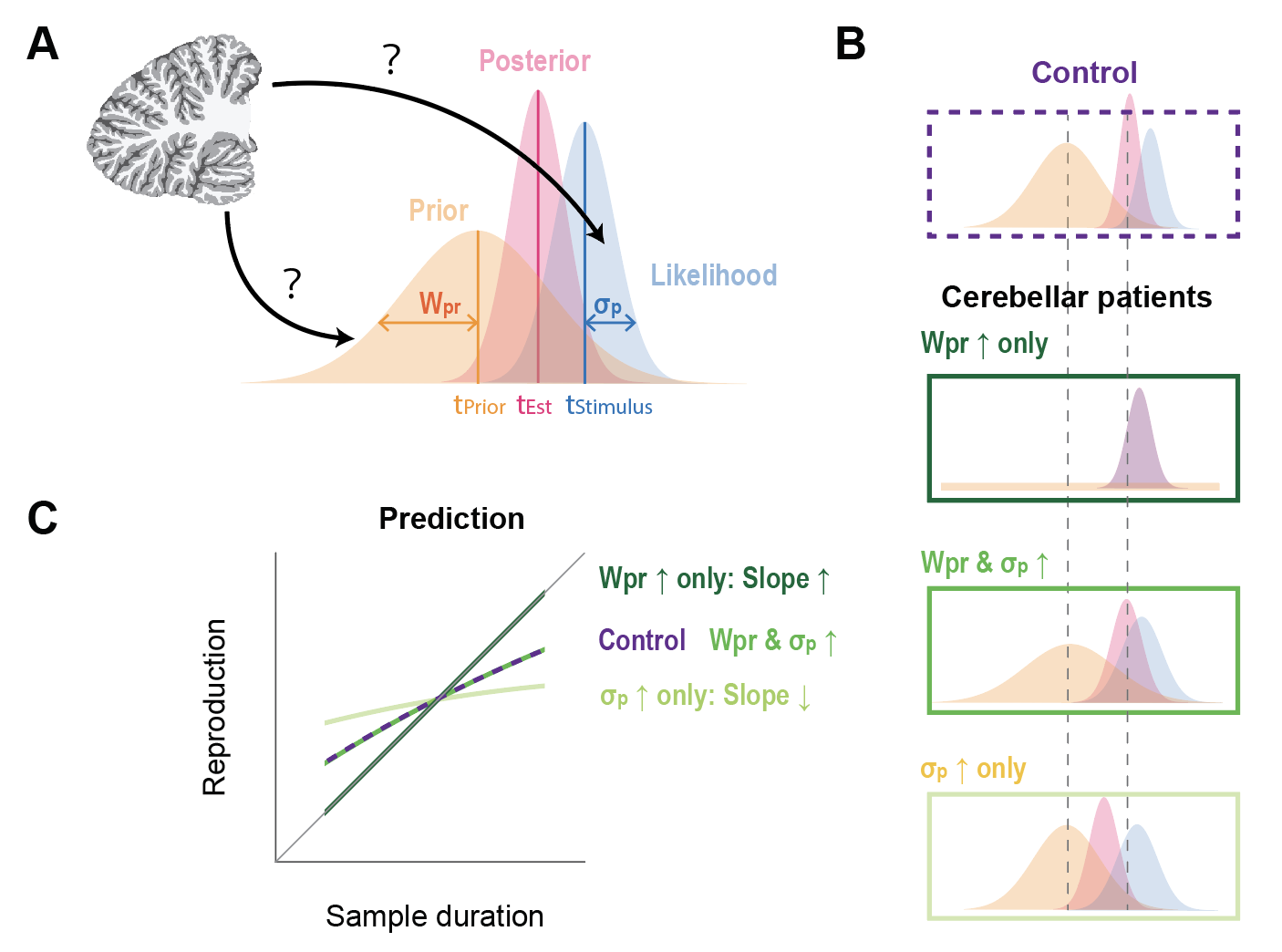

- Timing has been considered a core cerebellar function. We focus on whether the cerebellum encodes the likelihood, the prior, or both in time perception.

- A domain-general hypothesis of the cerebellum is that it is involved in continuous operation (as in motor control and timing). I examine this idea using the intuitive physics tasks, which require mental simulations in a continuous space.

- While clinical work has suggested the critical role of the cerebellum in social perception, it is less clear what specific aspect of social function has been impaired in patients. We expanded on previous work to examine how cerebellar patients are impaired in emotion perception, face perception, and the theory of mind tasks.